|

|

|

||

|

|

Chrysler workers manufacture trucks for the Canadian Air Force, ca. 1939 - 1945 Courtesy of Windsor Star, P8956 |

|

Canadian Motor Lamp employees, ca. 1944 Courtesy of Rose Kurek |

|

Aerial photo of Ford of Canada strike-area at noon, after union officials began to clear away the auto blockade, 7 November 1945 Courtesy of Art Gallery of Windsor |

|

Auto blockade and picket lines outside the Ford head office, 6 November 1945 Collection of Archives of Labor & Urban Affairs, Wayne State University, Courtesy of Art Gallery of Windsor |

|

View of auto blockade from the underpass leading to Wyandotte St., 6 November 1945 Courtesy of Art Gallery of Windsor |

|

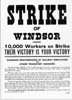

Handbill from the Canadian Brotherhood of Railway Employees, 1945 Courtesy of Walter P. Reuther Library, Wayne State University |

|

Excerpt from The New York Times, 7 November 1945 Courtesy of Windsor Public Library See attached picture |

|

R.C.M.P. officers mount their horses outside of what appears to be Kennedy Collegiate Institute, 6 November 1945 Courtesy of Walter P. Reuther Library, Wayne State University |

|

R.C.M.P. officers flown from Ottawa dissembark from their chartered plane, 5 November 1945 Collection of Windsor Star, Courtesy of Art Gallery of Windsor |

|

Cheque covering dues paid under the Rand Formula by Ford of Canada to UAW Local 200, 1947 Courtesy of Public Archives of Canada, PA115269, Courtesy of Art Gallery of Windsor |

|

Tag showing support for Local 200 Courtesy of Walter P. Reuther Library, Wayne State University |

| U.A.W. Local 200 member's

hat, n.d. Gift of Daniel LaRiviere, Collection of Windsor's Community Museum, 996.21.1 |

|

| The

Helen E. "picket boat" patrolling the Detroit River outside the Ford

of Canada during 1945 strike, October - November 1945 Collection of Archives of Labor & Urban Affairs, Wayne State University, Courtesy of Art Gallery of Windsor |

|

|

Workers from Motor Products Corporation picket Ford of Canada in support of UAW Local 200, 1945 Courtesy of Public Archives of Canada, PA31232, Courtesy of Art Gallery of Windsor |

|

Henry Howarth in sound-car used to boost the morale of picketers, 2 November 1945 Collection of Windsor Star, Courtesy of Art Gallery of Windsor |

|

By 1937 General Motors had signed the first auto-industry contract in Windsor, but the movement to organize auto workers did not gain its full momentum until Canada entered World War II in 1939. The government enacted strict regulations to manage the wartime economy and the production of arms. These regulations called for the compulsory conciliation of labour disputes and stipulated that work stoppages could not occur while a dispute was being investigated. Picketing was deemed illegal and wages were all but frozen. A patriotic workforce was at first willing to comply with government admonitions to "sacrifice" but it saw no forfeiture on the part of auto companies who were garnering record profits from the production of war materials, and effecting speed-ups in the name of patriotism. It was not long before Canadian auto workers decided to act, exploiting a labour shortage unparalleled in the history of the industry. This was a rather awkward and contradictory environment in which to act, however. When workers at Chrysler demanded union recognition and a collective agreement in 1940, the company did nothing. It instead locked out sixty-two workers later that year over protests regarding unjust seniority practices. While over three-thousand men continued to work inside the plant, picketers outside were arrested and subsequently found guilty of violating picketing laws. An arbitrator appointed to investigate the situation could do little but strongly urge Chrysler to re-hire the dismissed men as there was no legislation to force companies to comply with suggestions. The question of recognition remained unsettled, and it was not until May of 1942, almost two years after the initial request for union recognition, that an agreement was finally reached. Sometimes efforts went more smoothly as in the case of workers at Ford. In response to a formal request for union recognition in October of 1941, the company offered its own union, which it promoted via newspaper ads, radio spots and personal letters sent to employees' homes. The UAW did much of the same. In a vote taken 13 November, 1941 a majority of workers voted to support the UAW, and by January of 1942 an agreement was signed. Without even striking, workers attained union recognition of their new local - Local 200, a shop steward system to investigate and negotiate grievances, and the first forty hour work week. Not long after the successes at Ford and Chrysler many smaller industry feeder plants demanded and were granted union recognition by their employers, and a strike wave in 1943 encouraged the government to make union recognition and compulsory collective bargaining law. By 1945 the UAW had fifty-one-thousand members in Canada and was the largest industrial union in the nation. However, union recognition did not bring automatic improvements in working conditions; speed-ups continued, strict workplace rules of conduct remained intact and minor abuse and favouritism by foremen were still a fact of factory life. When ten-thousand Ford workers struck on September 12, 1945 they had more than fulfilled their patriotic obligations. They wanted a closed shop and dues checkoff - the automatic enrollment of all employees in the UAW and compulsory withdrawal of union dues from workers' paycheques. While negotiations continued and proposals were rejected, the strike dragged on. By November, Local 195 voted to stage a sympathy strike that eventually closed twenty-five plants and put an additional eight-thousand workers on the picket lines. A decision to close down Ford's power plant gave striking workers a tactical advantage. No work could be done in the factories - even by scab labour - and more importantly, the factories were without heat. The prospect of millions of dollars in damage to private property as autumn turned to winter precipitated a government decision to send 125 mounties to Windsor to handle the situation. The mounties did not get their men; they were repelled by an auto-blockade that covered twenty blocks around the plant and focused world-wide attention on the situation in Windsor's auto factories. Public outcry following the blockade led the government to appoint Supreme Justice Ivan C. Rand to arbitrate the dispute. His ruling, known today as The Rand Formula, stopped short of granting workers a closed shop, but did make dues check-off compulsory. The Rand Formula was a milestone in labour-management relations and remains an integral part of collective bargaining in Canada. |

|